Mind in the Machine

Can Deep Learning Approximate Brain Function?

I wrote the following essay as the course project for the Minds, Brains and Machines class of the Master in AI at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona Spain.

Introduction

The ultimate goal of deep learning is to create a system, that can solve any problem a human can. In order to achieve this lofty goal many advances in neuroscience and artificial intelligence are still needed. In this report I go over the relationship of deep learning and human brain function. I present a comparison of popular deep learning building blocks, such as convolutional layers or recurrent networks and present their biological counterparts - dendritic spiking and short-term memory. Later, I discuss neuroscience theories and research such as a theory of mind pattern recognition, brain simulation and mapping.

Section 1 concentrates on background information of deep learning, brain regions and single neuron models. Section 2 focuses on theories and research in neuroscience as it relates to artificial intelligence.

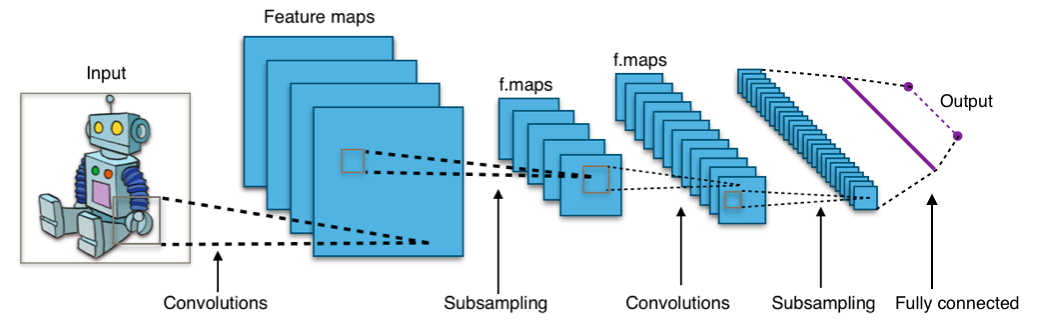

Fig 1: Typical diagram of a convolutional neural network (Wikipedia)

1 Background Information

Deep Learning

In recent years an explosion has been witnessed in the machine learning community. That explosion is the growing popularity of deep learning. It has been used for varied tasks such as computer vision and natural language processing. The main concept of deep learning is to build computational models with multiple levels of abstraction just as humans do when conceptualizing new ideas or knowledge. Most deep learning methods are built with neural networks.

The origins of neural networks and deep learning were in fact biologically inspired and go back to the 40s and 50s - McCulloch and Pitts (1943), Hebb (1949) and Rosenblat (1957). Deep learning techniques have gained power with the advent of backpropagation and recently have become widely utilized due to increasing computational power and GPUs.

Convolutional Neural Networks

Currently deep learning is characterized by the varied successes of CNNs in varied fields. CNNs are a deep feed-forward neural network that is inspired by the visual system of animals and by receptive fields in particular. Hubel and Weisel showed an early example of how the primate visual system functions. Later, such knowledge was incorporated into the AI field.

Typically a CNN consists of the following elements:

- Convolutional layer - this is the core building block of CNNs. A single discreet convolution on an image represents a receptive field of an animal visual system. A convolution is performed by comparing the learn-able filter kernel with the receptive field of the image. It results in an activation of the image to that particular filter.

Equation 1: 1 dimensional convolution of continuous variables:

f(t) * g(t) = ∫−∞∞f(τ)g(t−τ)dτ

Equation 2: 2 dimensional discreet convolution (where M,N is the matrix size):

f(x,y) * g(x,y) = ∑_n_1 = 0M∑_n_2 = 0Nf(n1,n2)g(x−n_1,y−n_2)

Pooling layer - the max pooling layer is a type of sub-sampling. This function is necessary for reducing the number of parameters and for building levels of abstractions with a smaller number of parameters (smaller resolution).

Nonlinearity - a nonlinear activation function is needed to increase the nonlinear properties of the neural decision functions. Some common functions are the rectified linear unit (ReLu) f(x) = max(0,x), logistic sigmoid function f(x) = (1+e−x)−1 and the hyperbolic tangent f(x) = tanh(x).

Fully-connected layers - fully connected layers flatten the pixel output of the convolutional part of the network into a flat neuron structure where each neuron is connected to a pixel of the previous part. The fully-connected layers are expected to learn latent variables of the data distribution.

Loss layer - the loss function models the difference between the model that the CNN builds and the true data distribution. While training CNNs the loss function is minimized - treating the learning problem as a mathematical optimization.

Backpropagation - after an error with respect to the loss function is calculated we can backpropagate through the entire network and update weight parameters of all neurons.

Regularization methods - bias/variance tradeoff and Occam’s razor state that the simplest solution to a problem is usually the best. Some of the common methods used for regularization are dropout, weight decay and L1 or L2 regularization.

Recurrent Neural Networks

A major weakness of CNN networks (and all other fully-connected networks) is the inability to handle sequences of varying length. Many interesting problems in speech recognition, natural language processing, stock market prediction and others can only be analyzed as time series data. In order to handle sequences of indefinite length, the neural network must maintain a memory-state of the data. The way RNNs handle memory is also biologically inspired - they provide a recurrence of it’s output back into the input of the neuron along with the input data. Artificial RNNs necessarily perform this operation in discreet time steps. However, the operation itself is reminiscent of self-autapses in a cell’s axon with it’s own dendrites. Continuous time recurrent neural models have been shown to learn vision in robotic systems analogous to animals. A major breakthrough of RNNs is the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cell invented by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997). LSTM manages to preserve input memory for very long sequences of data - making this network ideal for very deep learning of long sequences. LSTMs are used by over a billion people worldwide - in the form of speech recognition and text prediction in Android and iOS devices.

Generative Models

Most of the successes of deep learning are attributed to large labeled datasets combined with fast computers and supervised learning. Supervised learning requires labeled data to correct the model’s mistakes. However, most learning done by humans is unsupervised. Unsupervised learning was the main focus of research in the 80s and 90s, but it has largely been overshadowed by supervised learning. Researchers, see a return to the unsupervised way of making sense of the world using deep generative models DeepLearningBook, OpenAI Blog - Generative Models.

Generative models can provide a way of making sense of the world. Contrasted with discriminative learning, which only tries to calculate the probability of the output give the data P(y|x), generative models can provide an estimate of the real data distribution P(x|y). This allows sampling the machine representations of the input - these potential representations can be used to build “machine dreams” or the computers understanding of reality. An impressive use of generative models can be seen in the DCGAN (deconvolutional generative adversarial network) model to create images based on an output belief (Radford et al).

Brain Regions and Brain Mapping

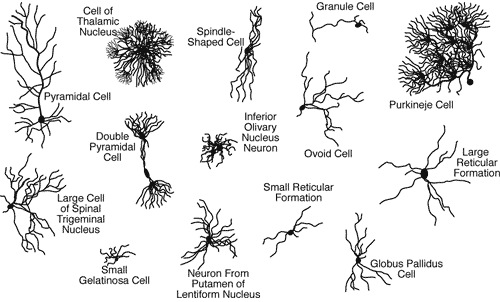

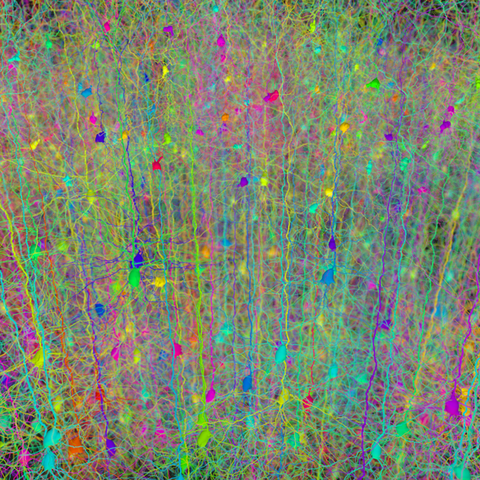

The human brain is more complex than any artificial system created so far. An adult brain has around 100·10⁹ neurons and 10 times as many glial cells. Rough estimates of the number of synapses and dendrites (tree-like structures with synapses on them) are 10¹² and 300·10⁹ respectively. These estimates are an approximation due to the variation in the types of neurons in the brain as seen in Figure 3.

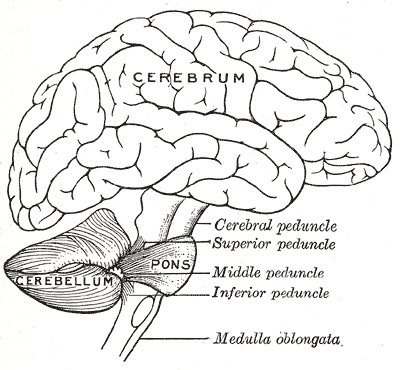

Fig 2: Cerebellum and Cerebrum

Fig 3: Different types of neurons in the brain

Cerebellum and Cerebrum

The two main regions of interest in analyzing brain computational complexity are the cerebellum and the cerebrum. The cerebellum (Latin for little brain) is the motor control complex of the central nervous system. It is densely packed with 3/4 of all of the neurons of the brain. Many of them are packed with dense Purkinje cells (which have upwards of 10⁶ synapses each). However, most researchers used to think that the cerebellum is the primitive part of the brain (solely responsible for motor control and involuntary action) and only recently some research has shown that the cerebellum has links to intelligence differences among mammals.

Whereas the cerebellum can be considered as the supercomputer of the brain the cerebrum may be thought of as the creative center. As can be seen in Figure 2 it is much larger in size, it also consists of sparse neural connections. As in artificial generative models these sparse connections neurons provide the cortex the ability to organize conceptual information in different levels of abstraction. The outermost layer of the neural tissue of the cerebrum is called the cerebral cortex (roughly 2.4 mm thick). Large folded grooves along this layer greatly increase the surface area of this organ in humans and primates compared to other mammals. The larger surface area of the folder grooves allows greater volume given a constant thickness of 2.4 mm (compared to a hypothetical smooth neocortex).

Necortex

The outermost layer of the cortex is called the neocortex (so named because it is the most recent to evolve). It is commonly known as gray matter. It has been shown that this part is responsible for conscious thought, language and spatial reasoning. In other words the neocortex is the main driver of human intelligence and abstraction. The neocortex is split into 6 layers. Layers II and III have axons which project to other parts of the neocortex. Layer IV receives input from outside the neocortex (mainly from the thalamus). Layers V and VI have axons which are connected to other parts of the brain: thalamus, brain stem and spinal cord. Much of the regions are of the neocortex are very specialized towards the function of that spatial region of the brain. For example: layer IV changes thickness (of input) depending on the area of brain specialization - in the occipital lobe (responsible for visual processing) layer IV has a very complex structure just to handle the input of visual data.

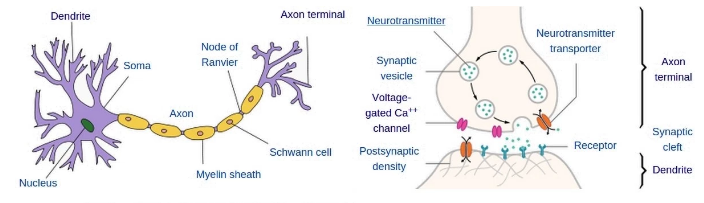

Fig 4: Left: diagram of a neuron. Right: Axon terminal and dendrite of next neuron.

Cortical columns and mini-columns

Large regular, repeating patterns of neuro-cellular structure have been observed within the cortex. Vernon Mountcastle has termed these patterns cortical columns (Mountcastle, 1978). Follow-up by Hubel and Weisel that found similar repeating patterns in the visual system of monkeys (along with further investigation) won the 1981 Nobel Prize in medicine. Each column consists of roughly 60·10³ neurons and there are 2.5·10⁶ columns in the neocortex. The existence of even smaller units of organization has been hypothesized. These units are called the mini-columns. Each mini-column is said to contain about 100 neurons. With this estimate there would be roughly 300·10⁶ mini-columns in the brain. In Ray Kurzweil’s book “How to Create a Mind”, Kurzweil shows that the human brain is capable of storing roughly 300·10⁶ patterns giving weight to the idea that the mini-column is the basic unit of pattern recognition and that the brain may utilize the same kind of regular organization that artificial neural systems use.

Single Neuron Models

Analogous to transistors the single neuron is the smallest unit of computation in the brain. Unlike transistors, a single neuron is an extremely complex system itself. Some of the complexities include protein signaling and genetic manipulation. Modeling a single neuron can be more complex than modeling the abstracted processes of brain learning. In fact one of the outstanding questions of computational neuroscience is: what level of abstraction is satisfactory for modeling brain function without the minutiae.

Neuro Transmitter Analysis

Synaptic vesicles (as seen in Figure 4) carry neurotransmitters within them before spilling them out into the synaptic cleft where:

They may find a receptor protein on the dendrite of the post-synaptic neuron.

A protein could disintegrate them in the synaptic cleft.

A protein could pull it back into the axon (re-uptake) of pre-synaptic neuron.

The first two model a process that is similar to multi-layer perceptrons ∑wixi + bi and the last is somewhat reminiscent of RNNs.

Once inside of the dendrite a neurotransmistter generally acts to open asu channel for ion flow into the dendrite. Less commonly it may bind to a G-protein and produce a signalling cascade that can:

Regulate a gene to produce new proteins, that integrate in synaptic surfaces (neuron body, dendrites) - this is related to learning and plasticity.

Signal proteins to change the spatial structure of the dendrites and synapses. This is like dynamically changing the architecture of a neural network - something very difficult to do in artificial networks.

Dendritic Spikes

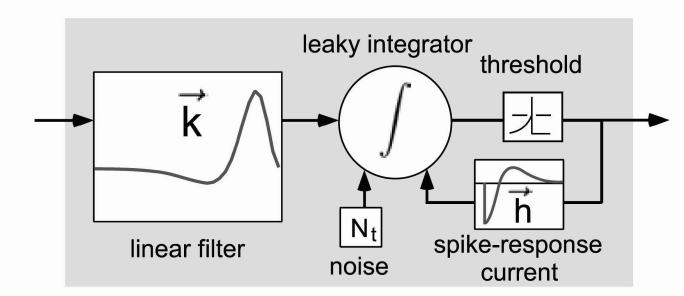

Dendritic spikes occur when enough dendrites have received synaptic signals to produce action potentials (spikes) that can propagate through to the neuron soma. Originally modelled as linear summation of weights by McCulloch and Pitts, they have since been shown to have an element of nonlinearity. Some of the newer models of dendritic spikes are LNP - linear/nonlinear Poisson models and leaky integrate-and-fire models. Both models are relatively simple, but can provide an element of nonlinearity to the decision function of the neuron. Figure 5 shows both the integration of previous inputs (analogous to convolution as seen in Equation 1) and recurrence of previous outputs (as in RNNs). In some ways a single neuron is more complex than a single convolutional layer in a deep learning network. However, it has not yet been shown that all of this complexity is required for learning.

Fig 5: Leaky integrate-and-fire model of neuron spiking.

Neuro-encoding

As noted in the subsection above, most models of information flow in the brain use the neuron action potential as the basic unit of information. This view ignores some of the complex protein and DNA interactions (further investigated in Protein Signaling and Genetic Manipulation), they also ignore single neuron effects and the action potential height and width variations. Having said that, spikes provide a good reference for investigating brain function. Complex sequences of spikes (spike trains) are termed neuro-codes in the neuroscience literature. A code can represent the time-series input to a neuron or the neurons output. Temporal locking in response to visual stimuli has been observed, suggesting that spike patterns are an acceptable abstraction of low level brain function.

2 Deep Learning vs the Brain

Similarities between Deep Learning and the Brain

Many similarities between brain function and deep learning have been noted. This is a good sign, it means the AI community is on the right track towards achieving human like performance in machine learning problems. One can think of the similarities between brain function and deep learning as a sort of reinforcement-learning signal to deep learning research. In this sub-section I will highlight some of the similarities between deep learning and the brain.

Convolution as Dendritic Spikes

The role of convolutional layers in deep learning was explained in Convolutional Neural Networks. Also, a brief overview of dendritic spikes was given in Dendritic Spikes. It becomes clear that the neuron-dendrite model is at least as complex as a convolutional layer. In fact, the commonly used methods for modeling dendritic interactions in neuroscience are the LNP and the integrate-and-fire models (Figure 5). The two models can be thought of as a summation and an integration respectively, just like the convolution equations described in the convolutional networks section.

The pooling operation in ConvNets can be contrasted with the dendritic spike induced voltage-gated sodium channel influx. This happens when neurotransmitters connect to the dendrite of the post-synaptic neuron and open a channel for sodium ion flow (see dedicated section). This causes the dendrite to rapidly depolarize and it may affect nearby dendrites and potentially the whole neuron. The essence of this action is that a sufficiently strong signal can overwrite nearby dendrites causing them to spike at the same time, which is just like the max-pooling operation.

Nonlinearity is inherently built into the behavior of single neurons as can be noted in LNP and integrate-and-fire models. Since a single neuron may have a complex, nonlinear decision function we can infer that the whole network inherits further nonlinearity.

Fully connected layers of CNNs can be simply modeled as the multilayer perceptron, which in itself is based on the neurotransmitter to synapse interactions of the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neurons.

Recurrence and Short Term Memory Models

The feedback loop in recurrent neural networks is based on neuroscience research that tries to explain memory models. Some of the models that looked at memory are Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968), Baddeley and Hitch (1974). These models included recurrent feedback loops for short-term memory and mechanisms for offloading short-term memories to long-term storage. These recurrent short-term memory models directly inspired the Long Short-Term Memory by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997), which is one of the most used types of deep learning networks today.

Missing Complexities in Deep Learning

While there are many similarities between artificial neural networks and brain function there are just as many differences. For now deep learning methods fail to accurately model single neuron dynamics. Furthermore, most learning done by the brain is unsupervised as opposed to the supervised models of recent deep learning methods. Lastly, we are still not sure what the real “learning algorithm” of the brain is. There are many ideas about how to learn more about brain learning and I will discuss them in the following sections.

Protein Signaling and Genetic Manipulation

As briefly mentioned in the neurotransmitter analysis section neurotransmitters may enter the post-synaptic neuron and signal a gene to produce new proteins. These new proteins can then travel to other neuron surfaces(soma, dendrites, axons) and cause further signaling. This is called a protein signaling cascade. A neuron can regulate itself and other neurons on-the-fly in very complex ways.

Another factor is online genetic manipulation of the cell bodies. When a neuron receives a specific neurotransmitter it may cause the cell messenger RNA and DNA to recombine in different ways. These recombinations can entirely change the genetic makeup of neuron axons. They can move, grow or shrink (spatial modulation) or adjust their protein makeup that in turn adjusts the neurotransmitter generation in axon terminals (temporal modulation). This extremely complex behavior is not yet fully understood, and further research is needed to model genetic manipulation.

Unsupervised Learning and Sequence Prediction

We know that the brain learns largely in an unsupervised manner. What is more puzzling however is precisely how it learns. It is unlikely that one function can learn all that is needed. The No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem states that there is no single solution to every possible problem. This means that the brain can adapt its learning strategies in many cases. I will talk more about function optimization in the next section.

In the recent book “Surfing Uncertainty” from Andy Clark (2016), Clark notes that the input that humans receive from the outside world is very sparse. He hypothesizes that we are always trying to predict ahead of the input sequence. The argument is that if the brain had to wait to fully parse input it would never have time for action. Such predictions would be constantly flowing up and down the cortical columns (and mini-columns). In the model, a directed thought is both trying to predict the sequence of output of the thought as well as access stored patterns (memories) related to that thought. The closest deep learning alternative to this would be generative models as related previously.

Brain Learning as Cost Function Optimization

A recent article (still in pre-print) titled “Towards an integration of deep learning and neuroscience” by Marblestone, Wayne and Kording (2016,) raises many fascinating questions on the relationship of neuroscience and deep learning research. The authors argue that the brain performs complex cost function optimization and can change the cost function depending on the task.

They provide three main hypotheses which are addressed in the following subsections.

The Brain Optimizes Cost Functions

It has been noted that human (and animal) actions can sometimes achieve near optimal performance. An example would be fine motor control skills that have evolved to minimize energy while maximizing utility. This suggests that motor control skills are constantly being fine-tuned by the brain. Marblestone et al think that the brain can assign weighted credit to it’s learnable goals in a form of reinforcement learning. Furthermore, it must mean that these cost functions are highly tunable to different scenarios.

Cost Functions are Diverse

Since the NFL theorem states that a single cost function will on average have the same performance as any other cost function, any globalized learning must be able to adapt diverse cost functions for optimizing different problems. In simpler terms, it means that the brain must use different approaches to solving different problems. This has been observed in the differences between the visual system and attention models. It is also very likely that cost functions for one area are calculated by another area of the brain which is in charge of setting goals for the first one.

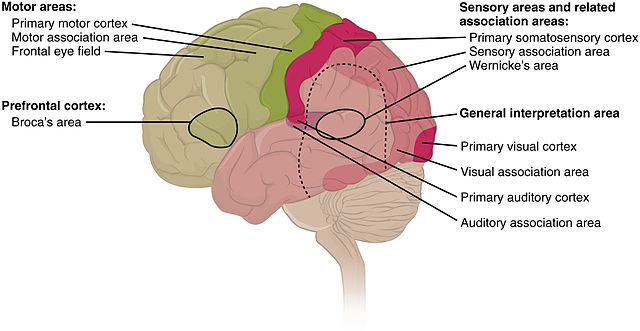

Fig 6: Cortical areas by function

Specialized Brain Systems Solve Key Problems

Figure 6 shows the different areas of specialization of the neocortex. The models of these functional areas were verified by functionall MRI imaging. The figure shows that different brain areas specialize in solving different problems. This must mean that different areas are driven by different goals or functions. This hypothesis is further validated by the fact that patterns of information flow seem to be fundamentally different across different brain regions. This must mean that some complex interaction of single neuron dynamics, flow of information within cortical columns, flow of information into the thalamus (which is connected to layers V and VI can redirect information back into another region of the neocortex) are all somehow changing the underlying cost functions of the brain in different ways for each of the specialized functions.

Bridging the Gap

Despite all, the fact that neuroscience and deep learning are not quite on the same page suggests that the two fields have a lot to learn from each other. Neuroscientist can create and test hypothesis about brain functions that are not yet understood using techniques and models from deep learning. Deep learning on the other hand owes much of its successes to early work in neuroscience and still can still utilize bioplausability as a reinforcement signal for new deep learning ideas. That does not mean that an AI system needs to fully simulate all of the brain - just like planes do not fully simulate the way birds fly. Planes are, however, inspired by the same Bernoulli principle that birds utilize for flight. Perhaps to build more successful AI systems we need to learn some abstract and adaptable “learning algorithm” that we can then use in artificial systems.

Fig 7: Synthetic pyramidal dendrites grown using Cajal’s laws

Full Brain Simulation

The brain is a physical system with physical interactions, therefore it should be possible to emulate these interaction in silico. Figure 7 shows a visualization of synthetic dendrite interaction. Full brain simulation, of the type that is being developed by the EU Human Brain project right now, is an active goal of research. In the past many have hypothesized that simulating the brain (to a reasonable level of abstraction) can provide the basis for a strong AI system. The problems with such a system are of course the complex single neuron interactions, protein cascades, genetic manipulation and so on. With each added step of biological accuracy there is exponentially more computation needed. Another problem is the fact that interactions of different regions of the brain are generally modeled using differential equations. These equations cannot provide the essence of the signals flowing through them.

One way of validating signals flowing through the brain is to use functional MRI imaging of real humans and comparing the interactions with simulated brains. This is a very difficult task that will require tremendous amounts of data to analyze, but it is achievable and some of the best minds in neuroscience are working on it.

Pattern Recognition Theory of Mind

In Ray Kurzweil’s book “How to create a mind”, Kurzweil notes that the neocortex performs a pattern recognition role vital to human intelligence. Modern research agrees that the 6-layers perform a sort of unsupervised learning algorithm. Some attempts have been made to model the cortical interactions as message passing algorithms popular in probabilistic graphical models. These Bayesian interactions play well into Kurzweil’s pattern recognition theory of mind, which attempts to model the cortical-sheet learning using Hidden Markov Models.

An interesting update study was published by Bertrand du Castel (2015). Du Castel’s work says that the pattern recognition machines can be better represented by stochastic self-organizing grammars. Hidden Markov models are in fact a subclass of stochastic grammars. It has been shown that stochastic self-organizing grammars can model complex relationships such as recurrence and swarm organization.

With more work in understanding the organization of cortical-columns and mini-columns, the relationships between self-organization of these pattern recognizers and the cost-function optimization and goal setting of the neocortex, better neural models can be built for deep learning.

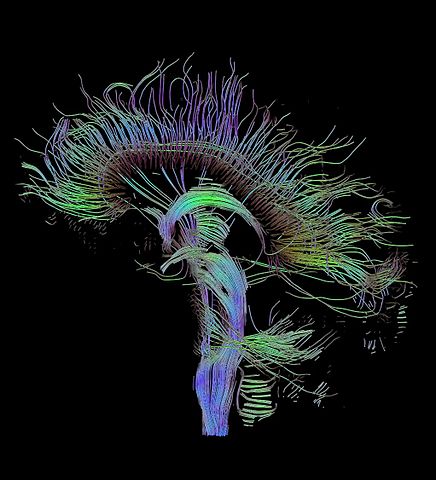

Fig 8: Tractographic reconstruction of neural connections via diffusion tensor imaging.

Human Connectome Project

The human connectome project aims to build a structural description of the human brain. It started as a research need for a common database of neurological data for neuroscientists. Recent advances in imaging and analysis techniques such as functional MRI, diffusion MRI and diffusion tensor imaging (see Figure 8) have allowed neuroscientists to create a rough ’wiring diagram’ of the brain.

Once created, this body of data will allow for further studies of brain disorders as well as building new theories about the connections and interactions of brain sections. The connectome can finally shed light onto the role of mini-columns in pattern recognition and prediction. Perhaps, soon a true theory of mind can combine the principles of self-organization, probabilistic pattern prediction and cost-function optimization.

Conclusion

This report discusses and compares recent trends in deep learning and neuroscience. I have focused on showing similarities between popular deep learning techniques such as convolutional layers, pooling, nonlinearity and provided their biological equivalents - namely the synaptic interactions between the axons and dendrites of neurons. It seems that convolutional operations are similar to the way the brain obtains abstract representations of patterns. This is a very promising for deep learning.

I have discussed new research and theories modeling brain function and what deep learning is still missing. Deep learning is however catching up; an example are deep generative models which can build abstract relationships about the world in an unsupervised manner much like the brain.

I have mentioned the difficulties in modeling complex biological properties of brain function. However, in order to build a true theory of human brain learning we only need to understand an abstraction of the biological processes.